Oscar 2024 | South cinema’s global ambitions

https://th-i.thgim.com/public/life-and-style/ayiple/article67388218.ece/alternates/LANDSCAPE_1200/A%20still%20from%202018%3A%20Everyone%20is%20a%20Hero.png

The name Samikannu Vincent might not ring a bell among contemporary filmmakers, but his century-old methods to bring the magic of motion pictures to people, certainly would. In the early 1900s, this unassuming railway employee from Tamil Nadu, after a chance meeting with a French film exhibitor, procured a projector and a bunch of films. He then lugged them across India, and as far as present-day Pakistan, in what became one of the first attempts by a South Indian to showcase films (albeit foreign ones) outside their region.

By the latter half of the last century, films from the South were making their presence felt at global film festivals, with the likes of Adoor Gopalakrishnan — whose debut Swayamvaram competed at the Moscow International Film Festival in 1973 — being the trailblazers. The veteran Malayalam filmmaker often contrasts the cumbersome processes of those early days to the present when things can be done online through platforms such as FilmFreeway.

Veteran filmmaker Adoor Gopalakrishnan

But no matter the ease of submission, winning awards is a whole other ballgame. And the Oscars has been India’s white whale. After S.S. Rajamouli’s RRR win last year (for Best Original Song), thanks to an expensive lobbying push, hopes are high for the Best Foreign Language Film category. Are they justified though, without equally deep wallets or the know-how to wrangle a strong PR and lobbying team in Hollywood?

A still from RRR

| Photo Credit:

PTI

This year, Malayalam film 2018: Everyone is a Hero is India’s official entry at the 96th Academy Awards. The survival drama directed by Jude Anthany Joseph, based on the deadly 2018 Kerala floods, is the third from the South to be selected for the honour in the past four years, after Pebbles and Jallikattu.

South Indian films have had an okay run across the pond; till date, 15 films have been picked, out of a total of 56 submitted over the years from India. But most of them, except the multi-lingual Hey Ram, were not seen by too many from outside their own states. Things are different now, with the current crop of mainstream and independent films gaining a large viewership outside their home states thanks to subtitling. The success of Baahubali, Drishyam, K.G.F, Pushpa, RRR and other films in the North have also spurred an interest for content from the region among the OTT platforms and film distributors.

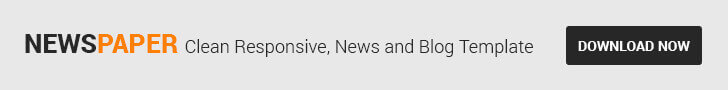

But it is not enough. Tamil filmmaker P.S. Vinothraj, whose debut feature Pebbles won the Tiger Award at the International Film Festival Rotterdam in 2021, recalls personally sending out entries to festivals (which were initially rejected) before being picked for Rotterdam. “In a way, the Rotterdam award, which paved the way for more international festival invites, helped Pebbles in getting noticed in India, too,” he says. “Such small films can dream of visibility in the country only by winning something overseas.” The film was India’s official entry for the 2022 Oscars and though Vinothraj had a fair idea about how to approach film festivals, he “didn’t have a clue about the Oscars, and could not go there to campaign”.

Director P.S. Vinothraj

A still from Pebbles

Stories that resonate

For a long time, films from South India used to be grouped under the catch-all term of regional cinema, while Bollywood was considered to be synonymous with Indian cinema, especially in the global circuit. Recently, however, aided either by bigger budgets, strong content, astute marketing, or a combination of these — such as K.G.F and RRR tapping new markets by appearing on popular TV shows and tying up with social media influencers in the North — things have begun to change.

“Currently, there are films from the South that are qualitatively better than the rest, both in mainstream and independent cinema,” says filmmaker Girish Kasaravalli, chairman of this year’s Film Federation of India’s (FFI) Oscars selection committee. “Earlier, exposure to world cinema was quite limited, while now we have 20-30 film festivals in India. People who are exposed to literature and various socio-political movements, and with a broader outlook, are also getting into films.”

On the face of it, Pebbles might seem like a film that defies western expectations of Indian cinema — something that movies such as RRR satisfies with its lavishly mounted song and dance sequences. But at a time when stories that resonate lived realities are prized, the film, which is firmly rooted in the arid rural landscape near Madurai and draws on deeply painful personal stories, speaks a visual language that can communicate with audiences anywhere.

Telugu filmmaker Venu Yeldandi’s Balagam (one of 22 films screened for FFI’s selection committee) is of a similar nature. Set around a death and the ensuing family drama, the film is a hit in Telangana and is making the rounds at film festivals, including the Swedish International Film Festival. “It is a situation that anyone, anywhere can relate to. Although the culture might be different, the emotion is the same,” explains Yeldandi, adding that he has “learned a lot from watching Malayalam cinema, especially how they create gripping cinema from simple ideas. With OTT platforms opening up the brilliance of South Indian cinema to the rest of the country, it has also helped improve the cinema literacy of emerging filmmakers from here”.

Venu Yeldandi (right) on the set of Balagam

A still from Balagam

The people to call

The last few years have thrown up a few big names who are helping facilitate the international stretch of an Indian film’s journey. For RRR, the Oscar campaign was helped along by film consultant Josh Hurtado as well as distributor Variance Films headed by Dylan Marchetti, who is currently pushing Lokesh Kanagaraj’s Leo in the U.S. markets. Producer Guneet Monga, a long-time associate of filmmaker Anurag Kashyap, with experience of taking Indian films to international festivals, led the charge for this year’s Oscar-winning documentary The Elephant Whisperers.

The Malayali excursion abroad

The Malayalam film industry, meanwhile, is markedly moving away from the larger-than-life, mass masala entertainers that were the mainstay till the noughties. From Dileesh Pothan’s Thondimuthalum Driksakshiyum, Geethu Mohandas’ Moothon and Lijo Jose Pellissery’s Ee.Ma.Yau and Jallikattu to Rajeev Ravi’s Njan Steve Lopez, the films exude a new sensibility, ranging from realistic stories of everyday people to raw and edgy tales. The fact that much of this has been achieved within a mainstream format has helped them attract a new set of audiences outside Kerala, as well as make a mark at international festivals.

Filmmaker Mahesh Narayanan, whose Ariyippu (2022) became the first Indian film in 17 years to be selected for the main competition at Locarno Film Festival, says the arrival of OTT platforms and their assurance of accepting original content gave him the courage to do the film. But it comes with its own drawbacks. “One of the issues is that all the top tier festivals insist on getting the premier show. So, we have to delay the theatrical and OTT release, which can be a difficult proposition,” says Narayanan. “Also, a film that works in one region might not work in another, like Ariyippu which had a better reception in Europe as compared to the U.S.

A still from Ariyippu

Learning how to navigate such markets is essential to getting more eyeballs — something that will need specialised help. But an ecosystem of programmers to help project movies from the South to international film festivals is yet to emerge. Producers are also reluctant to shell out money to send films to major festivals, each of which has a hefty entry fee (approximately €300 each) if it is not by invitation. “We hardly have any homegrown programmers or initiatives like a proper film market to bring in curators of major festivals and international film publications to take our cinema to the outside world,” says veteran director Gopalakrishnan. “Though such an initiative was launched at the IFFK [International Film Festival of Kerala] a few years back, it did not take off. [The International Film Festival of India’s Film Bazaar, however, has been relatively successful over the past decade in helping films finding buyers in abroad.]”

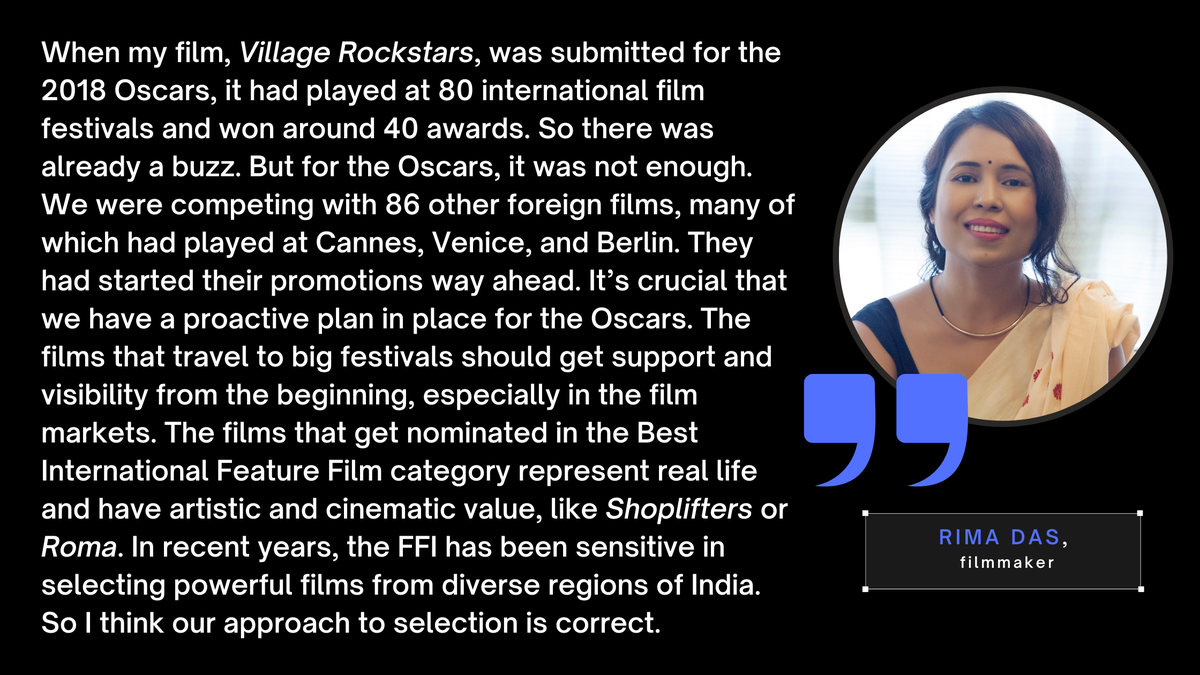

So, how can one bridge the gap? What is the next step for India, and a film from the South, to make it big? Meenakshi Shedde, who does South Asia programming for the Berlin, Toronto and Jio Mami Film Festivals, and was a Golden Globes International Voter in 2022-23, says that films are primarily selected on merit and the programming team’s tastes. There is a dramatic increase in the number of Malayalam films at top festivals now because there is a much wider range of talented directors, including women.

Meenakshi Shedde

“I don’t believe Indian films should be tailor-made for the Oscars or any other award. For the Oscars, you need to make a great film, then hire a great U.S. festivals and awards publicist, and have the bucks to fund your campaign. RRR was backed by a strategic and systematic carpet-bombing awards campaign in the US, with global visibility,” she says. “It can be challenging for a first-time filmmaker to navigate the festival circuit, but it need not be so. A filmmaker simply needs to make a list of the film festivals they can target, and match the specific category of their film — be it human rights festivals, LGBT festivals or environmental festivals.”

Draw of the Diaspora

For those that fail to get into the top tier film festivals, the emergence of diaspora festivals has become a major attraction. But it is difficult terrain to navigate. According to festival programmer Bandhu Prasad, who played a role in taking Ariyippu to Locarno, new festivals crop up every other year, and some have hardly any audience or stature. “Part of the job is identifying which festival to send each film to. Quite a lot of niche festivals have now emerged. For instance, Amal Prasi’s Baakki Vannavar — on the struggles of gig workers — was chosen for Construir Cine, the International Labour Film Festival in Argentina, this year,” says Prasad.

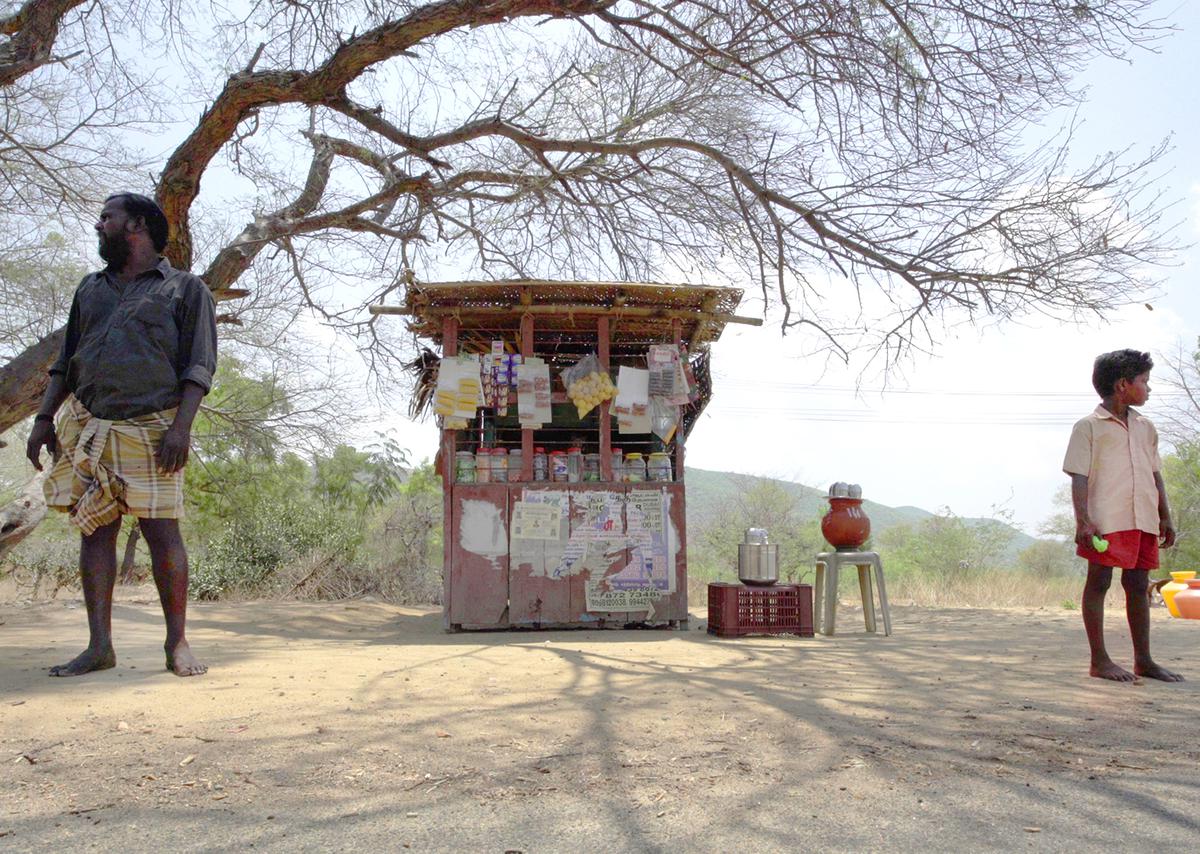

Working for the Oscars

Out of the 1,500-plus films being made in India across languages, producers of only 45 applied for the Oscars selection process this year, out of which 22 were finally screened, says Ravi Kottarakara, president of FFI. A majority don’t apply, he says, as they are aware of the costs involved after selection, be it the PR campaign or lobbying the academy voting members, which would set them lighter by a minimum of ₹15-₹20 crore. Most are content with the attention a film gets as ‘India’s Oscar entry’; however, last year’s marketing push by the RRR team is now encouraging some producers to think about attempting something similar.

Venu Kunnappilly, one of the producers of 2018, says that filmmakers and producers from Kerala have now begun thinking big, too, especially with regards to pitching at film festivals and award shows such as the Oscars. They don’t want to limit themselves to just a state award or local ticket collections, as overseas markets and OTT rights add a good share to the film’s total revenue.

A still from 2018

“Being the country’s official selection at the Oscars would make campaigning easier than if it were a direct entry [producers can enter their films directly in the main categories, like RRR did]. We did not initially think of pitching it for Oscars, but the overwhelming audience response and record collections from the U.S. and U.K. markets made us go for it,” he says. “A few promoters have already contacted us, but we are yet to take a call. Over the next two months, we will start the campaign, focusing on subjects like climate change which the film deals with.”

Amid all the buzz about ‘pan-Indian’ films from the South, the filmmakers quietly making their way through international festivals with meaningful content are still learning to negotiate the territories.

praveen.sr@thehindu.co.in

With inputs from Shilajit Mitra