Inside Ukraine’s largest textile company, which was transported from Poland

https://img.pravda.com/images/doc/7/4/7426910_fb_image_eng_2023_11_08_00_42_08.jpg

Prior to 1991, light industry accounted for up to 20% of Ukraine’s GDP. Now that figure is less than 1%. There is only one thread factory in the country, and fabric manufacturers can be counted on the fingers of one hand.

The market leader in Ukraine’s light industry is the Textile-Contact Group, owned by Oleksandr Sokolovskyi, a well-known blogger in the business world. Sokolovskyi’s regular Facebook posts about entrepreneurs’ success stories, abuses by government bodies and the arbitrariness of law enforcement agencies have an extensive readership.

Publicity is an excellent tool, Sokolovskyi says. He has long since retired from operational management and is now involved in strategic processes, including lobbying for the interests of Ukrainian manufacturers.

Advertisement:

A combination of business acumen, luck, and bidding in major tenders has enabled his company to become the No. 1 player. But industry leadership has not guaranteed the Textile-Contact Group the status of a big business or made Sokolovskyi a multi-millionaire. Why?

Textile-Contact is the largest operator on Ukraine’s textile market. The group has divisions that import, manufacture and trade fabrics, haberdashery, workwear and accessories. The group consists of 12 manufacturing enterprises in Ukraine, retail outlets, and an online store. There are over 30,000 fabrics in the range.

Starting out: selling handmade blouses

Sokolovskyi, a welding engineer by trade, started out in business in Mariupol by selling clothes made by his wife, Olena. Their parents had given them a sewing machine – a Chaika-132 – as a wedding present. “In the late 1980s, the cooperative movement began [when thanks to Gorbachev’s reforms, it became possible to run a small business in the Soviet Union – ed.]. My wife was good at making her own clothes, and we realised we could make them for others. There was a huge shortage of consumer goods in those days,” says Sokolovskyi.

In 1989, the couple moved to Kyiv, and Sokolovskyi’s wife taught him how to sew women’s blouses in popular designs. He would sew 20 blouses in the evenings after his main work and at weekends, then sell them himself.

“An engineer’s salary was 200 roubles a month, and I used to earn 800 roubles selling blouses. My parents were engineers too, and we lived modestly, so I could only have dreamed of earning that kind of money,” the businessman recalls.

At first, Sokolovskyi tried to sell his garments at markets – the Patent market near the Olympic Stadium and the Yunist on Perov Boulevard. That didn’t work out. Then he obtained a permit to set up a stall at a more central location, under the arch at the corner of Khreshchatyk and Liuteranska Streets. “I took some wooden crates from a vegetable shop, covered them with oilcloth, and laid out my blouses. There was plenty of passing trade and no competition nearby. Even the gangsters collecting their ‘tribute’ weren’t interested in me,” he says.

Subsequently, the then-mayor of Kyiv, Leonid Kosakivskyi, kicked out all the street vendors from Khreshchatyk. Sokolovskyi moved to Starovokzalna Street, near the Light Rail terminus. It was at that point that he decided to expand. He took on his brother and sister, Vadym and Kateryna Vechorek, as assistants, stopped doing the sewing himself, hiring homeworkers to do it instead, expanded his product range, and started sourcing and purchasing fabrics.

“My competitive advantage was finding good fabrics that were generally in short supply. To buy them cheap, you had to buy in bulk. I sold the surplus on to other seamstresses and tailors,” Sokolovskyi says.

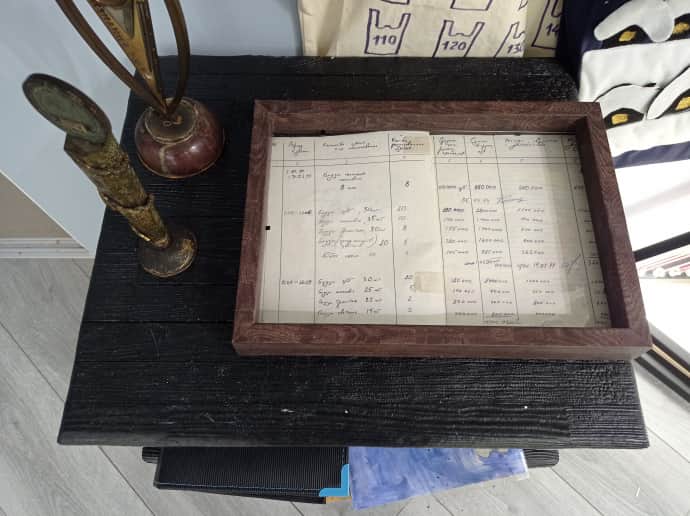

An accounting ledger for 1994-1995. Photo: the Textile-contact Museum

PHOTO: OLEKSANDR KOLESNICHENKO. EKONOMICHNA PRAVDA

In 1995, as well-known foreign chains began to enter Ukraine, Sokolovskyi felt that the time for bespoke tailoring was ending. It was time to look for another niche. The answer was plain to see: reselling fabrics made more money than selling clothes.

At that time, China had not yet become a major supplier of fabrics. Sokolovskyi would buy material from the Donetsk Cotton and Paper Mill, the Darnytsia Silk Mill, and factories in Ivanovo, Russia, and Belarus and Uzbekistan. Trading with the latter was done in a way that was typical of those days: barter. Sokolovskyi sent a truckload of sugar to Tashkent first, and he received a truckload of fabrics back.

Textile-Contact’s first steps

Sokolovskyi registered Textile-Contact as a company on 1 April 1995. He opened an office in a rented room in the premises of a former kindergarten in Berezniaki on the outskirts of Kyiv. The start-up capital was US$10,000.

The barter schemes with Uzbekistan expanded, with the Ukrainians selling powdered egg, buckwheat, Berezhany glass, fire engines from Pryluky, perfumes, and packet kissel (jelly). They later switched to direct purchases and expanded the list of suppliers and the range of fabrics. “We’d rely on large stocks so that the sewing workers didn’t have to wait. We didn’t do any dumping, we didn’t have the lowest prices, but we always had the maximum selection of goods in stock,” says Sokolovskyi.

Textile-Contact allowed many of their customers to defer payment, essentially giving them credit, the businessman recalls. This enabled them to build a reputation as a reliable partner.

Gradually the company expanded into new areas: manufacturing its own fabrics, opening stores and sewing facilities, and producing home textiles, haberdashery and workwear. Later, Sokolovskyi moved away from operational management and appointed a managing partner for each new division.

“I take on strategic planning functions to help management when there are problems with large orders, tenders, ‘raids’ by law enforcement agencies, the business climate, or internal conflicts. I believe it is possible to maintain a balance,” he says.

Buy Ukrainian, pay Ukrainians

Sokolovskyi estimates that there are hundreds of large clothing companies in Ukraine, and thousands of medium-sized and small ones. However, not all of them have been able to invest in production engineering and development. “Until 2020, no one understood why we were developing clothing businesses. Everyone said that the US and the EU were moving production to China, where it’s cheaper. And then when Covid-19 broke out, Ukrainian manufacturers experienced a renaissance,” Sokolovskyi says.

Textile-Contact opened a clothing factory in Korosten, northern Ukraine, five years ago

PHOTO: OLEKSANDR SOKOLOVSKYI’S FACEBOOK PAGE

The group’s investment in production facilities enabled it to keep generating revenue when retail trade collapsed, thanks to orders from the Ministry of Health in 2020 and the Ministry of Defence in 2022. This meant the group could hire more staff, increase production volumes, and pay a record UAH 280 million (approx. US$7.77 million) in taxes in 2022. The tax burden for the Textile-Contact group of companies is 15% of turnover.

Until 2022, the company imported tarpaulin from Russia because none was produced in Ukraine and shipping from China was expensive. Russia accounted for less than 1% of the group’s imported raw materials. Now the company has launched its own tarpaulin production at its plant in Chernihiv.

Reverse relocation

In March 2022, the Russians hit Textile-Contact’s factory in Chernihiv. It had been operating there, in rented premises, ever since the group lost control of the Donetsk Cotton and Paper Mill in 2014. This mill used to produce two-thirds of Ukraine’s cotton fabrics.

The Chernihiv factory was badly damaged by the missile hit: cotton combusts like gunpowder, so the second floor of the building, where the equipment was, was completely burnt out. Chernihiv’s proximity to the Russian border proved to be no deterrent to the company’s managers. They repaired the roof, purchased additional equipment, and increased fabric production by half as much again.

A missile strike damaged Textile-Contact’s branch in Zaporizhzhia in October 2023. “This is still a ‘before’ photo, but I assure you that a more optimistic ‘after’ will soon follow,” Sokolovskyi says.

PHOTO: OLEKSANDR SOKOLOVSKYI ON FACEBOOK

Textile-Contact Chernihiv (TC-Chernihiv) now produces over 90% of cotton fabrics in Ukraine. Until 2016 the company had been in competition with Ternopil-based Texterno, but Texterno fell into a decline after the death of its owner, and Ternopil residents signed a petition to hand over its premises to Elon Musk for a Tesla Motors plant that would manufacture lithium-ion batteries.

Fabric production accounts for 15% of Textile-Contact’s turnover, and this figure is set to increase soon.

Oleksandr Sokolovskyi at the Future of Ukrainian Exports forum

PHOTO: EKONOMICHNA PRAVDA

At the Future of Ukrainian Exports forum organised by Ekonomichna Pravda, Sokolovskyi announced that he had bought a defunct textile mill in Poland and moved the equipment to Chernihiv, in a deal worth US$1.4 million. The new machinery will enable the company to create 80 jobs in Chernihiv, triple its fabric production, and produce 260-cm-wide fabrics, compared to the current limit of 180 cm.

It’s an unusual deal for a Ukrainian entrepreneur. Most have been diversifying their businesses over the past two years by opening branches abroad. What prompted Textile-Contact’s managers to take this step?

Managing partner Volodymyr Martseniuk first suggested the deal, with Sokolovskyi initially sceptical about the idea. “We considered rebooting the plant in Poland, but that would have required us to move to Poland and live there: to oversee production, look for people, arrange supplies, and disrupt our focus on the Ukrainian market,” he said.

The company’s team faced a choice: either to move and work for the Polish economy, or to stay in Ukraine. They chose the latter. “Volodymyr decided we would manufacture fabrics in Chernihiv, despite the risks. It ultimately paid off,” Sokolovskyi pointed out.

Once the equipment – which is being transported to Ukraine in 30 trucks over the next few weeks – has been installed, Textile-Contact plans to significantly reduce its imports of Turkish, Chinese and Pakistani bedlinen. The acquisition of the Polish processing plant will lead to import substitution by tens of per cent.

Defence Ministry tender challenges

“Everyone here is a patriot in words, wearing vyshyvankas [Ukrainian embroidered shirts, a national symbol of Ukraine – ed.], but never when it comes to helping Ukrainian manufacturers. Please, all things being equal, choose domestic products. We’ve been dealing for decades with the fact that the state always favours deals that come with a ‘sweetener’,” Sokolovskyi says.

Like other Ukrainian manufacturers, in 2022 Textile-Contact acquired the largest customer in its history – the Ukrainian Ministry of Defence (MoD). The pressing demand to equip, feed and supply the military kept businesses afloat and prevented the state from collapsing.

“The state machine worked exceptionally well when there was a real threat of occupation, and people were not afraid to take responsibility, and no talk about corruption came up at all,” the businessman recalls.

This favourable environment for domestic business lasted for six months. Then the Ukrainian MoD switched to purchasing uniforms from Türkiye at inflated prices through intermediaries in the autumn of 2022 and the first half of 2023. “Many officials lost their sense of danger as the war wore on. They behave as if they don’t believe in Ukraine’s victory, striking while the iron’s hot,” Sokolovskyi says indignantly.

The fall in military orders caused light industry to shrink significantly in 2023.

Sokolovskyi is pinning his hopes on Ukraine’s Defence Procurement Agency and its head, Arsen Zhumadilov, who earned his stripes at the State Enterprise Medical Procurement of Ukraine. What with the scandals and the appointment of its new deputy ministers, the Ukrainian MoD has pretty much halted procurement.

Adjacent to the EU, but not in the EU

Is it possible for light industry to develop without government orders? Sokolovskyi believes it is, since many Ukrainian companies are EU-oriented. “There are factories that operate independently of government contracts. Their equipment and their employees’ skillsets are tailored to Western demand,” he says.

Textile-Contact makes uniforms for the German police, clothes for commercial brands, and mattresses and blankets for the Baltic states. Sokolovskyi says trust and long-term cooperation contribute to receiving such orders.

The businessman hopes the deterioration in the West’s relations with China will galvanise a shift of orders to factories closer to the EU. “If the US placed just 1% of orders withdrawn from China in Ukraine, Ukrainian garment workers would be snowed under with work for years. The war is hindering this for now,” Sokolovskyi said.

PHOTO: OLEKSANDR KOLESNICHENKO, EKONOMICHNA PRAVDA

Ukrainian companies have a competitive advantage: the salaries in the industry, in the regions where the factories operate, are among the lowest in the country. According to Ukrainian employment website work.ua, the minimum pay for a seamstress at Textile-Contact is UAH 9,500 (roughly US$250) per month, with the average wage in Ukraine being UAH 14,000 (roughly US$390) per month. According to Sokolovskyi, seamstresses’ wages in Poland are not much higher, and their workload is greater.

He adds that EU governments often subsidise businesses in light industry, compensating investment costs and providing tax breaks. He does admit, however, that his business will be more profitable if Ukraine remains a candidate for EU membership for a long time to come.

“Poland prepared 3,000 negotiators for talks with Brussels before joining the EU. They fought with the bureaucrats for every point. Ukraine, unfortunately, signed everything it was presented with. It’s very important to be in the EU politically, but in terms of the economy, I don’t see any benefits from joining,” Sokolovskyi admitted.

The businessman believes being “EU-adjacent” will allow Ukraine to become a manufacturing hub: “We will be free from restrictions and can remain appealing to customers. It’s not even about low salaries. Our per-unit costs are higher due to anti-raiding costs and a complex tax system.”

How to avoid becoming a “little Russia”

Sokolovskyi has never been on the list of the wealthiest businessmen. He considers Textile-Contact to be a medium-sized business rather than a large one. Is making a fortune in light industry impossible? “The market is rather small. The majority of light industry products consumed in Ukraine are imported. And these imports are brought in on the grey and black markets,” he stressed.

Smugglers enjoy a simplified taxation system. Sokolovskyi gives an example: a decade ago, his group paid the same amount of tax as Kharkiv’s Barabashovo market, yet Textile-Contact employed a hundred times fewer people.

Sokolovskyi’s experience of working in Ukraine has toughened him up, however, and he has no intention of losing any momentum. By purchasing the Polish equipment and transporting it to Ukraine, he will be now able to set up a complete fabric production cycle and reduce dependence on imports.

Sokolovskyi has also vowed to keep on tackling the issue of corruption in the judiciary and police, and he urges other entrepreneurs not to just roll over and support them. “If we do that, we’ll be no different from Russia, and big Russia will always win over little Russia,” he concludes.

Translation: Yuliia Kravchenko and Artem Yakymyshyn

Editing: Teresa Pearce

#Ukraines #largest #textile #company #transported #Poland